100 billion / Federal budget / German climate finance

Poor outlook for USD 100 billion target – new financial commitments from Germany needed

The German government needs to make new pledges for climate finance. Photo: R.Moriz on www.flickr.com

Current analyses highlight several urgent works-in-progress in international climate finance. The industrialized countries are likely to fall short of their USD 100 billion target for climate finance. And while Germany is on track to meet its doubling commitment, it has not made new financial pledges for the time after 2020.

OECD: climate finance is increasing, but USD 100 billion target is not being met honestly

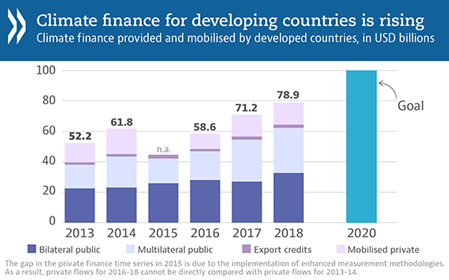

On November 6th, the OECD published its latest survey on climate finance provided to developing countries by industrialized countries, a study based on the numbers from 2018, the most recent reliable figures available. While it indicates a further increase in funds provided on the way toward the USD 100 billion target, growth has slowed considerably relative to the increase from 2016 to 2017. If growth in 2018 had continued at the rate of increase from 2017 to 2018, then we would be at around USD 94 billion in 2020, i.e. the USD 100 billion target would not be met.

Source: OECD 2020

Oxfam’s 2020 Climate Finance Shadow Report, which was published prior to the OECD report, estimates actual climate finance to be significantly lower – around 37% of the “official” figures – which is partly due to the predominant practice of counting the total volume of loans to developing countries instead of their grant equivalent. In addition, the question of what should be credited as climate components in projects remains a controversial issue. Applying that 37% to the USD 78.9 billion, the actual amount would only be about USD 30 billion. In view of the great need for climate action, it would be necessary for the USD 100 billion to be composed mainly of public funds and for loans and other mobilized financial resources to be viewed as additional.

Finance for climate adaptation is clearly too low

According to OECD figures, only about 21% of the USD 78.9 billion in 2018 was earmarked for adaptation to the consequences of climate change, which will impact the poorest and most vulnerable developing countries most heavily. In view of the fact that it has been agreed several times in the UNFCCC process that mitigation (currently around 70% of climate finance) and adaptation should be balanced, this is far from sufficient. In addition, the particularly vulnerable groups of countries – the least developed countries (LDC) and the small island developing states (SIDS) – only receive around 16% of the total climate finance volume. Oxfam also criticizes the far too low share of adaptation finance and even comes up with yet lower figures.

There is no doubt that mitigation, i.e. concrete climate protection, must also be massively promoted to meet the 1.5°C target of the Paris Agreement. But this cannot come at the expense of adaptation, which is already giving many millions of people a certain degree of protection against the effects of climate change.

Germany must announce post-2020 climate finance commitments and increase budgetary resources

Climate change casts doubt on the survival of humanity. The urgency of the situation can hardly be overstated. In 2015, German Chancellor Angela Merkel pledged to double the public funds for climate finance from the roughly EUR 2 billion that were budgeted in 2014 to around EUR 4 billion annually by 2020. A current estimate is not publicly available at present. An Oxfam Germany Briefing, however, points out the creative accounting used by the German government that makes achieving this goal questionable despite an actual increase in recent years. At the same time, Germany has made no international statement on how its climate finance will proceed after 2020. The Paris Agreement set USD 100 billion as a minimum amount for the period from 2021 to 2025. The next few years will be crucial in the fight against climate change and in meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Germany should underpin its high standing in international climate policy – the inadequacies of its national climate policy are not the issue here – with new climate finance pledges and continue on the course it set by doubling climate finance between 2014 and 2020. This would mean a further doubling of climate finance from budget funds to EUR 8 billion in 2025.

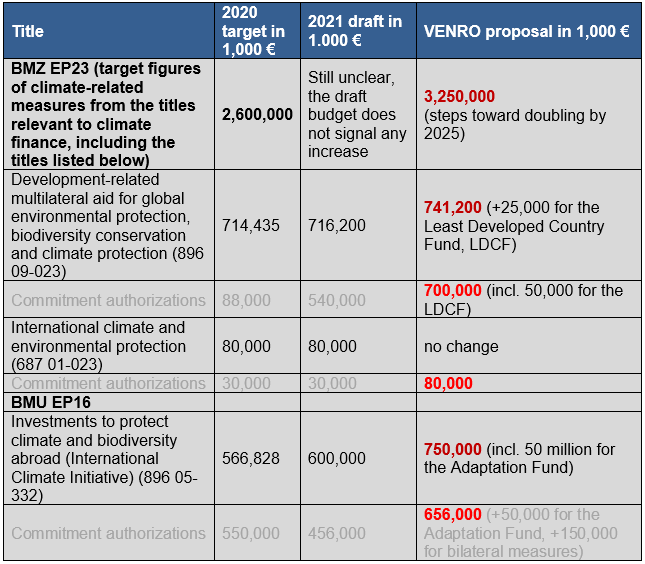

To this end, the 2021 budget must indicate the first steps toward growth. Unfortunately, this is by no means the case so far and must be corrected. From 2022 onwards, medium-term financial planning even provides for a decrease in corresponding funds. In a statement on the federal budget, VENRO therefore calls for the following changes, among others:

Source: VENRO: Statement on the 2021 GERMAN FEDERAL BUDGET: Draft for the 2021 federal budget and the financial plan until 2024. The proposed figures are shown in red.

Two upcoming climate summits as opportunities for new international commitments

The United Kingdom has already announced that it will double its climate finance by 2025 at the UN Secretary-General’s Climate Action Summit in 2019. The Climate Ambition Summit on December 12th, 2020 on the anniversary of the Paris Agreement that the UN Secretary-General and the British COP presidency announced in September would be a good occasion for the German government to announce a suitable commitment to up its game. Not only will the summit focus on stronger climate protection ambitions (e.g. through improved nationally determined contributions, NDCs), climate finance is also set to be a core topic.

In addition, Chancellor Angela Merkel has agreed to take part in the Climate Adaptation Summit, which will be taking place on January 25th and 26th, 2021 at the initiative of the Dutch government and others. This would provide an opportunity to pledge the necessary increase in adaptation finance as part of an overall doubling by 2025. This could be supplemented, for example, by very specific, high-quality initiatives for climate adaptation in developing countries including, but not limited to, support for women and gender groups that are particularly vulnerable to climate change in order to strengthen gender equality in climate finance. Such a commitment would also further increase the confidence of these countries in supporting more ambitious NDCs and promote an urgently needed climate policy dynamic, especially if, as is foreseeable, the industrialized countries in their entirety miss the USD 100 billion target.

The fact that a new German parliament will be elected next autumn should not be used as an excuse to postpone new commitments until then. After all, the doubling commitment of 2015 also played an important role over more than one legislative period. The next parliament will still be bound by the Paris Agreement, and it is difficult to imagine Germany withdrawing from its role as a key global player in the international climate debate – especially if the United States were to return as an active player in international climate policy under a new President Biden.

Sven Harmeling / CARE