The term “climate finance” in the narrow sense refers to financial support by industrialized countries to help developing countries mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the effects of climate change caused by global warming. Climate finance is based on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) of 1992, in which the industrialized countries pledged to support the developing world through new and additional funding to combat climate change. This obligation under international law has been confirmed by the Paris Agreement from 2015. It can be understood as part of a fair burden sharing in global climate protection based on the differences in responsibility in causing climate change and the (economic) capacity of the respective countries to curb it to the greatest degree possible and to adapt to the unavoidable consequences.

In a broader sense, the term often encompasses all public and private financing that serves to mitigate or avoid greenhouse gas emissions, transform energy systems, contribute toward climate-friendly development, assist in adapting to climate change, and recently also to manage unavoidable loss and damage arising from climate change – i.e. not only financial support for developing countries, but also the use of public funds at home as well as private (or public-private) investments.

The $100 billion pledge of the industrialized countries

It was not until 2009 that the UNFCCC’s general commitments were translated into more specific terms. Although the climate conference in Copenhagen that year failed on most of the key issues, it did see the industrialized nations committing a total of $30 billion in new and additional funding for the period from 2010 to 2012 as “fast-start finance.” Chancellor Angela Merkel pledged €1.26 billion as the German contribution to this sum.

In Copenhagen, the industrialized countries also promised to increase overall climate finance to $100 billion per year by 2020, mobilizing the required resources from public, private, and alternative sources. The question of how this promise was to be fulfilled was not answered at the time, and it remained a point of contention for many years in the UN negotiations for a new climate treaty.

Door countries apply a generous accounting method for this target which does not only include public funds of development cooperation, but also public loans, shareholdings and even export credits. In addition to this, donor countries also count the private investments mobilized with public money towards the $100 billion pledge.

In 2016, industrialized countries presented a roadmap indicating how they intend to meet their $100 billion pledge. Yet this was not met. In 2020 the level of climate finance was only around $83 billiion. In a roadmap published in 2021 the new target year for the 100 billion is 2023.

Main points of criticism are both the methodology by which the industrialized countries generously chalk up available or mobilized funds, thus artificially inflating their figures (more on this here) as well as the fact that only a relatively small share of the funds is dedicated towards adaptation to climate change.

Climate finance under the Paris Agreement

Under the Paris Agreement, climate finance continues to be one of the key areas to achieving the international community’s goals of limiting global warming to below 1.5°C, and in particular to helping the poorest and most vulnerable countries adapt to climate change. Article 2 of the agreement also requires all parties to reconcile worldwide financial flows with a development that is both climate-friendly and promotes resilience against climate change.

The international obligation of the rich countries to support poor countries financially already enshrined in the UNFCCC is thus being maintained in Article 9 of the Paris Agreement. A new aspect is that all other countries are also invited to contribute voluntarily to support poorer countries. Furthermore, it was decided in Paris to maintain the level of $100 billion a year promised for 2020 until 2025 and to set a new finance goal for the following years. This means that climate finance will remain one of the most important issues at the annual UN climate conference.

Climate finance channels and instruments

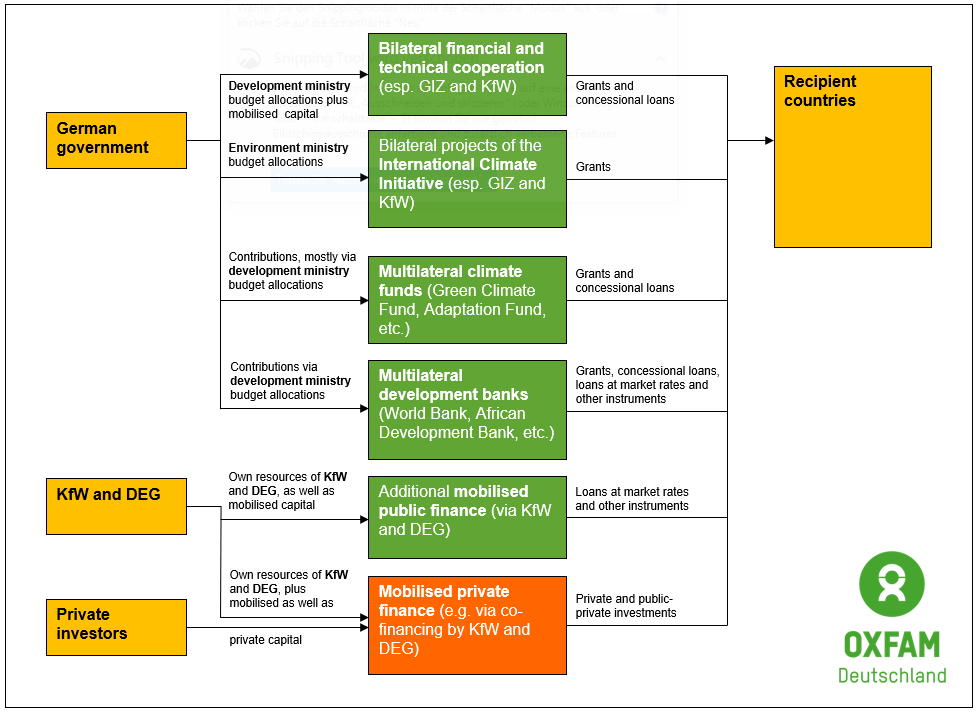

Rich countries use the traditional channels and instruments of bilateral and multilateral development cooperation in order to implement climate finance.

The largest share of climate finance (just over $31 billion annually in 2020) is provided through bilateral cooperation in the form of grants or loans that are often combined with or integrated in traditional development cooperation projects and programs. In the case of Germany, these are predominantly realized by the German Association for International Cooperation (GIZ) and KfW development bank. Bilateral climate finance mainly consists of grants and loans.

Channels and instruments of German climate finance

Schematic representation of channels and instruments of German climate finance, Source: Oxfam Deutschland, own illustration

A number of multilateral (climate) funds are also open to the donor countries, including the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Adaptation Fund and numerous other special funds. The multilateral development banks, whose budgets receive regular contributions from donor countries, are now also financing climate projects on a large scale using a wide range of instruments. The level of finance for multilateral channels is around $37 billion for 2020.

The industrialized countries would like to cover a significant share of their $100 billion pledge by “mobilizing” private investment. In 2020 this accounted for a total of $15 billion a year. These are primarily instruments in which KfW or other public actors create incentives for private investment through co-financing. While private investment can hardly be declared a contribution by the rich countries toward fulfilling their international obligations, they insist on crediting mobilized private investment toward their $100 billion commitment.

German climate finance

Germany also contributes to climate finance for developing countries. Most of the funds are made available through the bilateral development cooperation of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). A smaller (but important) share of climate finance is provided by the International Climate Initiative (ICI) of the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (BMUV). Furthermore, Germany regularly contributes to multilateral climate funds, including the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and the Adaptation Fund (AF). Germany also supports the budgets of multilateral development banks, which in turn finance climate projects.

In 2015, German chancellor promised to double public climate finance from around €2 billion planned for 2014 until 2020. However, the German government uses several tricks to implement this promise. This pledge was already fulfilled in 2019. In 2021, before the UN climate conferene COP26 the German government annouced at the G7 summit to further increase funding to at least €6 million until 2025. This refers to funding from budgetary sources (including grant equivalnts). The mobilized public funding is added separately to this sum. For the years 2022 and 2023 the German government has not forseen any increase to live up to its promis (see here).

Public climate finance from Germany

The green or green-hatched bars show the planned budget allocations, e.g. through bilateral grants or payments to multilateral. The funds “mobilized” on the capital market for climate loans by the development bank KfW and its subsidiary DEG are shown in orange. For 2022 and 2023 only the planned figures for budget allocations and grant equivalents, but not for mobilized funds. Until 2025 budgetary funds (plus grant equivalents) for climate finance should increase to €6 billion annually, mobilized funds are not part of this pledge. Yet, for 2022 and 2023 no increase is foreseen.

Germany remains a major donor. The German government has repeatedly emphasized that the country will make its fair contribution to international climate finance. While there is no internationally agreed basis for allocation of the $100 billion pledge, until recently the government internally considered Germany’s fair share to be about ten percent of the $100 billion; yet, this has never been publicly confirmed.In any case, the funds provided by Germany must continue to increase. Like the other industrialized countries, the German government does not intend to cover the German contribution solely with public funds, but to count private investment as well. These plans are highly problematic. They mean less public funding, and thus fewer opportunities to mobilize additional private investment, and ultimately less climate protection and less direct support for adaptation to climate change.

Implementation of climate finance

The German government has not yet presented a coherent climate finance strategy on how to support poor countries on climate change mitigation and adaptation. Quality and impact are at the center of this, but the fulfillment of quantitative commitments remains important aspects.

A basic precondition in this regard is transparency. A critical monitoring of German climate finance is not possible without information about what Germany is financing, who is involved in the implementation and the impact of the measures.

Climate finance is intended to provide lasting support for poor countries in taking a development path in accordance with the Paris Agreement and adapting to climate change. In particular, climate protection funds must not lead to the establishment of long-term emission paths that would lock countries into emission levels that, while lower overall, would still be deemed too high for the coming decades. From this perspective, investments in the energy sector that directly or indirectly contribute to keeping fossil fuels alive rather than swiftly replacing it with systems based on renewable energy are simply in direct contrast to the Paris Agreement. At the same time, the financed measures should also contribute to the overall sustainable development of a country and the fight against poverty, and thus needs to be embedded in and coherent with national sustainable development strategies and plans. Good climate finance also takes other aspects into account, including but not limited to gender sensitivity, a human rights-based approach and adequate participation by local communities and civil society, which is a vital prerequisite to aligning climate projects with the needs of people and anchoring them on the ground over the long term.