Loss and Damage / International climate finance

First Transitional Committee Meeting for new Loss and Damage Funding Arrangements and new Fund Showcases Major Fault Lines

Summarizing the results of the first TC meeting on Loss & Damage Finance. picture: UNFCCC/Liane Schalatek

hbsDC and others _submission to inform the work of the Transitional Committee_for TC2_FINAL

Climate change is causing widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages, with grave effects on gender and social equity, as the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) synthesis report confirmed in urging policy makers to action. Climate-vulnerable countries, in particular small island developing states (SIDS), and civil society have pushed for decades for financial support to help them address loss and damage as a matter of climate justice. After a historic decision at COP27 in Sharm-El-Sheikh to establish new funding arrangements, including a new fund for responding to loss and damage, a Transitional Committee (TC) with equitable representation of 14 developing and 10 developed country members, was set up to deliver concrete recommendations for a decision by Parties at COP28 in Dubai in early December that would quickly operationalize a new Loss and Damage Fund (LDF) and broader funding arrangements. The TC’s first meeting (TC1), held from March 27th to 29th in Luxor, Egypt, while not yet delving into too much detail, clearly laid out the major contentious issues and negotiating fault lines between developing and developed countries, despite efforts to carefully frame its work in the terminology of international responsibility and solidarity.

Broad mandate and tight time-table

The mandate the TC was given is broad with complex and interlinked issues focused on proposing new and improved funding arrangements for responding to loss and damage, designing the core structure and operational approach of a new fund, trying to find enough money to support the growing needs of developing countries to deal with those climate impacts they can no longer adapt to, and also making sure that new structures and approaches consider and complement the so far largely uncoordinated bits and pieces of funding support for loss and damage that are already happening. While developing countries want to focus on establishing the new fund first and foremost, developed countries, who have long resisted to establish a new fund focused on addressing loss and damage and to avoid any legal liability for climate damages, see a clear sequence with discussing the broader funding landscape initially, although none of the developed country representatives openly contested the need for a new fund. In Luxor, the TC heard presentations from experts from UN agencies, climate funds, development banks and humanitarian institutions on support relevant to loss and damage already provided, often in the aftermath of climate disasters, for example through humanitarian agencies, and an overview of how different agencies arrange for funding disbursement, including relevant triggers. The presentations also highlighted the enormous funding gaps that exit, such as for prolonged support for reconstruction efforts after climate disasters or preparing for long-term unavoidable climate impacts such as the relocation of communities due to sea level rise or cultures or ways of life lost.

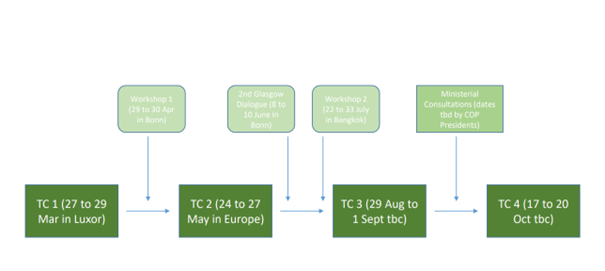

Ultimately, members committed to work on all four main issues (funding arrangements, the modalities for a new fund, funding sources and complementarity and coherence with existing financing approaches) under discussion jointly and in all meetings, rather than sequencing issues or prioritizing some over others. They will be supported in their work by a small TC secretariat as well as a Technical Support Unit (TSU) staffed with seconded experts from several existing climate funds, the World Bank, UN agencies and international humanitarian organizations. As its most important outcome, TC1, agreed on the way it will work and on an ambitious work plan involving three additional TC meetings and two technical workshops with a tight timeline, and selected two co-chairs, Richard Sherman of South Africa and Outi Honkatukia of Finland, both seasoned climate finance negotiators, to guide them through the year and keep them on task. How detailed the recommendations will be that the TC submits to the COP28 in December in Dubai for parties to consider and approve, will depend on who will carry the argument at the end of a seemingly technical TC process – to be cemented by consensus – in what is largely a political wrangling focus primarily on two key issue clusters. This will focus most prominently on whether those recommendations will detail a draft charter or governing instrument for a new LDF, laying out its core modalities and structure,

Focus and scale of the LDF

With the agreement, in principle, to work on making the LDF operational as part of broader funding arrangements as quickly as possible, there is disagreement on what the focus, and accordingly the scale, of the new fund should be. Developing countries, supported by civil society, envision an LDF providing funding for comprehensively addressing economic and non-economic loss and damage and covering both fast-onset events like climate disasters and slow onset events, like sea level rise to support actions related to all five R’s of recovery, reconstruction, rehabilitation, resettlement and resilience. In contrast, developed country TC members in their statements proposed a more surgical approach that determines where the existing gap in financial coverage for all actions related to loss and damage is and hone in on this gap as a priority for the LDF. Such an exclusive focus for example could target addressing slow onset activities only, as the representative of the United States seemed to suggest, and leave the response to climate disasters to humanitarian actors, development organizations and existing climate funds (especially, potentially the GCF) and prioritize strengthening their capabilities and the functioning of existing institutions first. With form following function, according to this argumentation this would result in a much smaller and less endowed fund than what poorer countries envision. Developing country TC members also expressed concerns that discussions focused on the “current landscape of institutions” and the “gaps within that current landscape” (which is in paragraph 6 of the decision given the Committee its mandate) will be used by developed countries as a distraction from getting concrete about the new fund itself, who should govern it, its operational modalities and how much funding it would need to do its work (at the heart of paragraph 5 of the same decision). At stake is also the relevance and scope of the new fund itself. Will it be one of many actors, a small side-kick in a ‘mosaic of solutions’ in the evolving financing landscape for addressing loss and damage, which for example includes the new Global Shield put forward by the German G7 Presidency at COP27, or be its center-piece with the function to coordinate and maybe help direct and rationalize the activities of others?

Eligibility and contributor base

The second big issue cluster of contention is who should receive money from the new LDF and who should put money into it. Developed country representatives want to reserve access to the fund to groups of developing countries they perceive to be particularly vulnerable, namely small island developing states (SIDS), least developed countries (LDCs) and fragile and conflict afflicted states (FCS) and exclude for example countries like China, Brazil, Saudi Arabia or India – which are categorized as developing countries under the international climate regime – from receiving support. Pushing a narrative similar to their efforts in the ongoing negotiations for a new collective quantified goal (NCGQ) on climate finance post-2025, they argue that in particular emerging market economies with higher incomes and better institutional capacities, given their own growing greenhouse gas emissions, should pay into the new fund as well and thus broaden the contributor base. Developing country TC members, including from China and India, vehemently pushed back by pointing to UNFCCC language and the principle of equity in looking at ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’ (CBDR-RC) of developed and developing countries, including in who needs to provide funding support to whom under this framework. Both sides haggled over the meaning of language in the decision that the new funding arrangements and the fund are ‘for assisting developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change’, a legal phrasing, which the international climate regime uses in other contexts as well and which developing country TC members stressed is not the same as talking about ‘particularly vulnerable developing countries’ with its intention to limit eligibility. In their view, shared by many civil society observers, this phrasing acknowledges that vulnerability to adverse climate change impacts and catastrophic loss and damage is not restricted to narrowly defined sub-groups of developing countries. A case in point is the massive 2022 floods in Pakistan illustrate, which cost more than 1,700 people their lives, affected more than 20 million people, and caused an estimated damage of at least US$ 15 billion, even without considering enormous reconstruction costs.

Stakeholder input and participation

While the TC1 was webcast [see here for day 1, day 2 and day 3 recordings] and meeting documents were made available to the broader public, only a limited number of civil society representatives were able to be on location, a consequence both of a late notification as well as some overly restrictive participation quotas (only three per UNFCCC observer constituency), which should be lifted for future TC meetings. Parties not represented in the TC and international organizations were also present. However, currently observers are not in the same room with the TC members but relegated to watch the proceedings from an overflow room and need the Co-Chairs special invitation to engage in discussions during the meetings. While the TC granted this opportunity during its first meeting day to hear from and engage with civil society participants representing women and gender groups, environmental groups, youth groups, and Indigenous Peoples and trade unions, and allowed for a short collective intervention on each of the other two days, it will need to discuss further at its next meeting on how to best bring in observers into the proceedings of the committee. Following the advocacy push by civil society in Luxor, the TC work plan invites observers to contribute with written submissions throughout the year to inform the discussions of the three more TC meetings to come. It will be important that all of these submissions will be transparently reflected on the committee’s webpage and not only be listed, but actually inform and be integrated in technical work.

Civil society stakeholders have much to contribute: they have experience engaging with and monitoring the operations of other climate funds such as the Green Climate Fund or Adaptation Fund and can provide analysis and suggestions on what lessons learned should be applied in designing the new fund, and thus greatly inform the technical deliberations. Through their presence, meaningful engagement and participation and critical monitoring of the process they can support its accountability, transparency and the safeguarding of process outcome and follow-up operationalization. They also work directly with affected communities on the ground and can amplify their voices, concerns and needs in pushing for a people-centered fund that promotes human rights and simplifies access to its funding for community-led actions, and prioritizes gender-responsive actions that support people’s rights to live and survive with dignity. Their representation and direct participation is crucial and should be financially supported through the TC process to the largest extent possible. Their expertise, including the lived experience of local communities and particularly affected population groups, such as women and marginalized gender groups, Indigenous Peoples, or the disabled in developing countries that have already suffered from losses and damages, should also be reflected in TC expert groups and discussions, such as its Technical Support Union (TSU) staffed with a growing cadre of technical experts seconded from multilateral development banks, UN agencies and international humanitarian organizations, which supports the TC members in compiling and synthesizing information and proposing approaches and structures, or in proposed workshops. CSOs’ continued advocacy over the course of the year will be necessary to ensure that the TC ends its work with recommendations leading to concrete outcomes, first and foremost a new LDF of scale and stature accountable to the international climate regime that is primarily resourced with public funding from developed countries and provides grant support to developing countries and directly to affected communities based on their needs and priorities for addressing loss and damage.

Next steps

With the first meeting ended the work of the TC ramps up. The TSU and a small TC secretariat will be busy compiling and synthesizing information, drafting background documents and preparing expert inputs, including a revised and reworked version of a mandated synthesis report by the secretariat on existing funding arrangements and innovative funding sources relevant for addressing loss and damage. TC members, but also countries not represented on the committee, and observers are invited to submit case studies on loss and damage and a first set of submissions on the issues under the mandate of the TC by April 25 to inform the discussions at the second meeting of the Committee, which will be held in late May (e.g. there is a submussion by Heinrich-Böll-Foundation). Already at the end of April committee members will convene for a hybrid technical workshop. And in June committee members will engage with the broader climate community under scheduled climate negotiations during the second Glasgow Dialogue session in June in Bonn.

Under the timeline (see the figure above), it is expected that the TC will already work on its draft recommendations at its third meeting scheduled for the end of August and share those for an added political push provided by a ministerial consultation in fall. These recommendations are then to be wrapped up at the TC’s forth meeting in late October, before they go to COP28 in Dubai in late November for the needed consensus approval by the COP and CMA.

Liane Schalatek, Heinrich Böll Stiftung Washington, DC

Read more: Find the submission to the TC by HBS here