Green Climate Fund (GCF)

GCF Board Approves the Fund’s First Eight Funding Proposals

The 11th Board meeting of the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which took place in Livingstone, Zambia, from November 2 – November 5, was one of nervous anticipation: just weeks before the high stakes climate summit in Paris, the 24 Board members faced their own high noon as they were asked to make history by approving the first set of eight project proposals worth USD 168 million in GCF support that would signal to the world and Paris negotiators that the new Fund was now fully operational. When the decision was finally taken – at 3:30 am on the morning of an extended last meeting day – the collective sense was one more of relief than of jubilation. Justifiable though, then the discussions and exchanges in Livingstone, among the Board members, but also between the Board and the Secretariat, made it clear that while technically the GCF might be fully open for business in a somewhat hastily constructed shiny new operations tower, the foundation of the building as well as its walls still need a lot of good policy reinforcement before the GCF can stand both the test of time and the test of its own ambition and strategic vision.

In a way, the work of the GCF Board and Secretariat over the past two years had targeted this exact moment: from the decision at the 5th Board meeting in Paris in October 2013 to set eight essential policy requirements for the start of the initial resource mobilization of the Fund, which were worked through in the first half of 2014, including by putting off crucial policy decisions on almost everything else; to the pledging conference in Berlin in November 2014 and additional commitments – as well as COP-guidance – received in the Lima COP 20; to the accreditation of the first 20 implementing entities for the Fund in the two prior Board meetings in 2015; to the feverish work of the Secretariat over a long summer and early fall to get from among the 37 full funding proposals received a set of eight ready for the Board’s consideration in Livingstone.

The First Set of Eight Funding Proposals

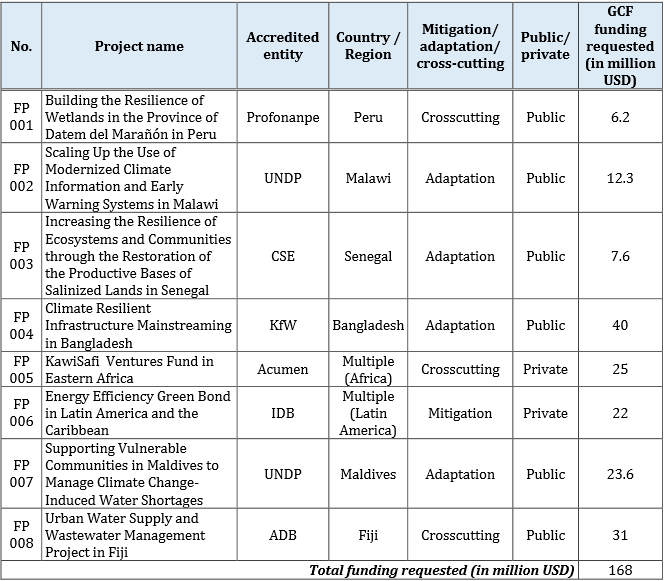

The balance of this first set of funding proposals up for Board consideration (see Table 1), although presented as accidental, was of course carefully calibrated to secure Board approval as a package – three from direct access entities, five from implementers with international access; two drawing on a wider spectrum of financial instruments beyond grants and loans with private sector involvement to tackle mitigation regionally; and four adaptation projects with heavy geographic focus on African states, LDCs and SIDS focusing on building cyclone shelters, reducing climate-change induced water shortages and improving the resilience of communities and ecosystems.

The proposals’ submission to the Board provided also a first test-case for the initial project approval process of the Fund, as well as its transparency, including for the work of the independent Technical Advisory Panel (iTAP) tasked to vet the proposals against six main investment criteria as well as the comprehensiveness of the due diligence check of proposals by the Secretariat against GCF fiduciary standards, environmental and social safeguards, its gender policy, overall risk management guidelines and the Fund’s results management framework. In presenting their respective assessment to the Board in open session, it was also clear that the iTAP and the Secretariat did not necessarily see eye-to-eye in evaluating the proposals.

In discussing this first set of GCF funding proposals, Board members were careful to point out that the projects would not set precedents, as several of them raised some fundamental questions both on process and contents.

- The Peruvian wetlands project for example drew concerns on whether Profonanpe, the Peru’s national implementing entity, obtained the free prior and informed consent (FPIC) of all Indigenous Peoples’ groups in the project area and whether Indigenous Peoples’ benefits and support can be ensured during project implementation.

- The impact of a CSE project supporting communities on salinized lands in coastal Senegal was questioned by the iTAP, mainly because the number of beneficiaries and the target area are small, prompting worry by observers that by falsely equating project scale with impact smaller community-based projects and programs could be put at a disadvantage in the GCF, despite their replication potential.

- With respect to the two water supply management projects in the Maldives and Fiji the iTAP questioned their adaptation relevance.

- A private sector project on energy efficiency bonds in Latin America and the Caribbean proposed by the Inter-American Development Bank which uses GCF funding as guarantee had some analysts worry about whether the involved green bond issuance will rely on the highest available international certification rather than just voluntary standards and exclude fossil fuel technologies completely. They also questioned the implicit promise for hundreds of millions in additional GCF funding for the same project over the next five years on procedural grounds.

- A project proposal submitted by Acumen for a regionally operating capital venture fund looking at raising risk capital for small-scale solar energy entrepreneurs in East Africa, which the GCF was asked to support with an initial equity investment, also raised some eyebrows because of a sequencing issue, as Acumen has yet to fulfill all the conditions of its accreditation.

Both private sector projects also expect to leverage additional financial resources by setting up special purpose financial vehicles in offshore tax havens, thus contribution to the international problem of tax avoidance, a practice that civil society observers decried as incompatible with the stated purpose of the GCF to be a paradigm shifting fund.

While the funding proposals themselves were generally welcomed by the Board, a few Board members from developing countries argued nevertheless for a postponement of all funding decisions to the next Board meeting. The almost failure of the carefully calibrated funding proposal package was due to their critical questioning of the overall progress in the GCF and their feeling of growing discomfort that in the mad rush to this decision point, the GCF has evolved further and further away from developing country Board members’ strategic vision of what the GCF should be: a fund, not a bank involved in highly structured finance, acting as an enabler for national implementing entities and country-owned strategic frameworks by delivering grants and highly concessional loans via direct access for concrete climate actions mindful and supportive of lasting domestic development needs.

Some Board Members’ Unease with Accreditation Results

The GCF accreditation process over the past year has reinforced the unease of many developing country Board members as well as many civil society observers that the Fund might not be able to move “beyond business as usual”, at least with respect to its implementing partners, by prioritizing direct access to GCF funding for national and regional developing country institutions. The balance and equitable representation of entities considered for accreditation between direct access entities, geographical/regional areas, private sector actors and international organizations is very much also at the heart of a strategic approach to accreditation that the GCF Board has yet to agree on.

The list of international access entities already accredited with the GCF reads like a “who-is-who” of big public development finance institutions: Asian Development Bank, World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and bilateral development finance institutions like Agence Francaise de Developpement and the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) – all of them accredited for large-scale projects (defined as up to USD 250 million of total project finance, including a smaller GCF share) in the highest environmental and social risk category A. In contrast, seven of the nine accredited direct access entities can only implement micro or small GCF projects (defined as up to USD 10 million or USD 50 million respectively), leading to fears that GCF funding could overwhelmingly flow through big development finance institutions thereby shoring up their business model rather than tilting climate finance delivery away from them toward national institutions.

A third batch of nine accreditation applicants for consideration in Livingstone, on which the Board deferred decision until March 2016, would have reinforced rather than ameliorated that trend, with the African Development Bank, the European Investment Bank and the Word Bank’s private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation, among the entities to be approved. The batch also included two large private sector commercial banks, HSBC and Credit Agricole. In contrast to the two earlier GCF accreditation rounds at the prior Board meetings, going into the Livingstone meeting, the identities of the accreditation applicants were known. This was also a reaction to the wide-spread criticism by outside observers to the accreditation of the Deutsche Bank at the 10th GCF Board meeting, who felt that the intransparency around GCF accreditation (justified with existing provisions under an interim GCF information disclosure policy, which was supposed to be revised in Livingstone but had to be postponed) impeded a thorough third-party vetting and independent verification of the applicants’ institutional track records. Pointing to the history of these commercial banking giants as being among the world’s largest financiers of continued fossil-fuel exploration and use, as well as regulatory compliance failures such as money laundering and human rights violations, many civil society groups actively engaging with the GCF had called for a rejection of the accreditation of HBSC and Credit Agricole to the GCF this time around. They doubt the sincere willingness of these multinational commercial banks to shift their entire funding portfolio beyond just a couple of choice GCF-supported projects, which they fear could be largely used in an effort to greenwash large commercial banks’ public image. Most developed country Board members disagree with this interpretation, arguing instead that an affiliation with the GCF, after having gone through its complex accreditation process, shows the commercial banking giants’ willingness to seriously begin a sustained shift of their financing in support of climate action.

Outstanding Operational Policies and Frameworks as Priority for 2016

How well the first eight GCF projects approved in Livingstone and dozens of future ones can be implemented will also depend on strengthening the operational foundation of the new GCF by tackling a number of accompanying policies and frameworks that were either not taken up or postponed over several Board meetings in order to fulfil the ambitious time-table that led to the consideration of the first set of full funding proposals just weeks before Paris.

The three Board meetings planned in 2016 (in early March, June and October) must tackle these outstanding policy issues and fundamentally strengthen the operational foundation of the GCF. Such policy reinforcement is necessary to ensure that the GCF is not only rapidly disbursing resources, but also capable of exercising due diligence for the effective and equitable implementation, scaling up and replication of GCF funded projects and programmes to the benefit of affected people and communities in developing countries and addressing their priorities and needs in a way that empowers national institutions, processes and communities and thus is truly transformational.

Liane Schalatek / Heinrich-Böll-Foundation North America

This is a short version of the article: “Relief not Jubilation as GCF Board Approves the Fund’s First Eight Funding Proposals”. The full article is accessible here.